Pass it on

Whenever we get the chance, Barbara and I revisit the spot where she accepted my proposal of marriage. It's even more special now as we approach our, um, golden years.

It was while living near San Francisco's Golden Gate in my early 20s that a wild and crazy Italian-American friend named John taught me how to fish for trout.

John lived in Sonora, a small town in the Sierra foothills of California. He and his family attended a church planted there by my good friends Larry and Joyce. One Sunday when I visited them, they introduced me to John.

From then on, any time I had a day or two off and enough gas money to get to Sonora, John would gladly take me trout fishing. I can’t remember what he did for a living, but I do recall that he never let his job interfere with sport.

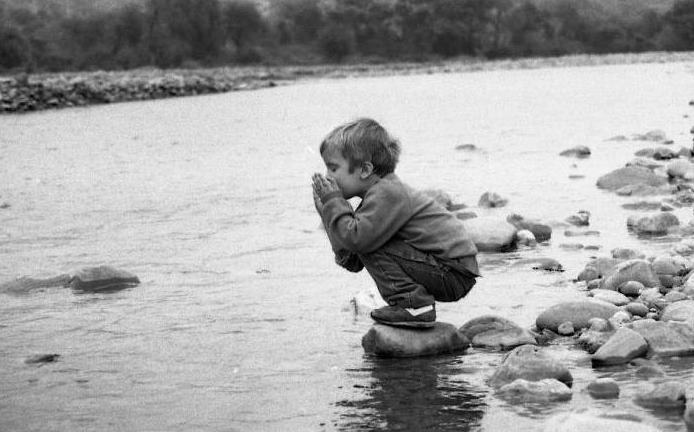

John set me up with ultralight gear, showed me how to choose favorable fishing holes, advised me on how to cast into them, and what to do when a trout struck. Being of Italian extraction, John shared these tips freely, energetically and often. It was never boring to fish with him, even if the fish didn’t bite. In hindsight, I suspect it was more the fun of exploring California rivers with John than the modest success I achieved as an angler that, um, hooked me on trout fishing.

So I confess right here that any trusted tips about stalking the wily Andes trout that you may have gleaned from these blogs owe their origins to my wild and crazy friend John.

The same goes for the origin of any tips about hiking, camping or operating a motorized vehicle at high altitudes. About 70 years ago, the places where we go fishing in the Andes were being explored by my missionary mentor, Homer Firestone. However, he didn’t do his exploring in 4WD SUVs, he rode horses. And his were not daytrips or even overnight stays. Homer’s excursions typically lasted two to three weeks.

Homer and his traveling companions did not carry fishing rods on these outings. They preferred shotguns instead, a necessity since they literally lived off the land while trekking between scattered indigenous communities.

They used the guns to hunt water fowl, conejos (known in North America as guinea pigs) and vizcacha. A tasty critter that looks like a cuddly jack rabbit with a squirrely tail, vizcacha build rock dens up near the craggy peaks of the Andes. You have to hunt them on purpose.

Few roads fit for motorized vehicles existed in Bolivia when Homer brought his bride, the former Elvira Englund, to the country in 1946. The couple settled in the capital, La Paz, where their two children were born. They moved to Cochabamba a few years later and remained there for most of the rest of their lives.

Homer once told me about the first overland trip in the Andes he made by motorized vehicle. He volunteered to help drive a small caravan of trucks and jeeps from La Paz to Potosi. Today that trip takes eight to nine hours over asphalt highways. It took Homer's crew roughly two weeks.

I say roughly on purpose. The party puttered painfully across the Altiplano on dirt tracks designed for sheep and llamas. They sustained three or four flat tires per day, an inconvenience that slowed progress yet further.

Decades later, rookie missionaries were still absorbing the hard lessons Homer and his cohorts had learned. When Barbara and I turned up in 1981, Homer advised us never to leave town without extra cans of fuel, since very few gas pumps existed outside the city limits.

He also suggested that, instead of steel belted radials, we should keep polyester cord tires on our jeep. Because they use inner tubes, these tires were the only kind that could be fixed anywhere in the country, provided you carried along tire patches and a hand pump. His hard-earned advice got us home more than once.

Of course, if I listed everything I learned from Homer Firestone, Ph.D., and his remarkable wife Elvira, their trusted tips would fill several blogs.

Less than one in 10 of my trips in the Andes involved stalking the wily trout. The vast majority were undertaken to preach the gospel. When he retired, I inherited Homer’s job of itinerant evangelist to Quechua and Aymara-speaking communities in the Andes highlands.

Barbara and the kids would sometimes come along. We followed a family policy that stated, “Anyone is welcome to join dad on preaching trips, but no one is ever required to do so.” I enjoyed a lot of company on these travels, all voluntary.

I recently asked our four children, now 30-somethings, what enduring lessons they learned growing up that they plan to pass on to their children.

Sarah, our eldest, immediately replied that her lesson is to make life-long memories as a family. She and husband Adam are making good on that project. Our three eldest grandchildren, still in grammar school, get to take trips to interesting destinations in the U.S.A. and enjoy a stream of creative family traditions dreamed up by their parents. This prompts Grandpa to keep reminding them that they are undoubtedly the luckiest kids in the world. (And don’t you forget it!)

Second daughter Molly said the first lesson that came to her mind is to always share the best of what you have with others, a kindness common to indigenous cultures in the Andes. “It still impacts me to think of how generously people who didn’t have much shared their best with us whenever we came around,” she said.

Carmen, our youngest, made a list. If you know Carmen, this does not surprise.

1. Enjoy natural beauty and don’t take it for granted. When you visit new places, take in the new scenery and don’t let it get old. Each place is unique and you may never see it like that again!

2. Always try new things--foods, places to explore, conversations to have. This is how you will get to know yourself AND how you will continue to grow and change.

3. Be grateful. Life can be tough at times so be thankful for all the good that is given to you.

Son Ben had the most to say, perhaps because he made the most trips to the mountains with dad. Starting at around age four he rarely missed a weekend excursion. This apparently stemmed from a sense of dutiful honor.

One Saturday morning, I was getting our tent and sleeping bags ready for another evangelistic campaign. Ben came into the room and said quietly, “Dad, is it okay if I don’t go with you this weekend?”

“Of course it’s all right, Ben,” I said, stopping to look him reassuringly in the eye. “You know the rule. You are always welcome to come along, but you never have to. It’s absolutely fine for you to stay home.”

I smiled and turned around to cram the last of my sleeping bag into the stuff sack. A moment later Ben said, somewhat apologetically, “It’s just that I don’t want you to get lonely out there, Dad.”

I dropped the sleeping bag to kneel down and hug Ben, but I couldn’t say anything because of the lump in my throat.

Ben told me this is what he learned on our Andes trips.

Humans are extremely vulnerable creatures and conditions can change instantaneously. You realize how miniscule you are in the scheme of things, how vulnerable to forces much bigger than yourself--elevation, terrain, weather, access to water and so forth.

Life finds a way to exist in whatever environment it finds itself. The Incas arriving in the barren heights of the Andes learned not just to survive, but to thrive. Humans are vulnerable but also adaptable.

I learned how extremely beautiful is this floating rock we live on.

I got a real kick out of the kid’s remarks. They are honest, accurate and wholly reliable. I also noticed that each is unique, just like my four children. No two of them look at the Andes world through quite the same lens, even though they all experienced the same Andes world while growing up.

I believe this has something to do with built-in diversity. If you believe, like I do, that God created the universe, then you have concluded, as I have, that God relishes variety. Think of what our planet offers in the way of diverse terrains, oceans, climates, and waterways, not to mention the myriad species of plants, animals, insects, fish and invertebrates that populate the earth’s vastly varied environments.

When you encounter the people that inhabit the planet, you find yet more diversity in language, custom, dress, music, legend and sport, all those things that make up the thousands of fascinating cultures human beings have devised.

The Bible plainly explains God’s motivation for creating this complex world. It seems He sends us messages every time we look at the earth and what’s in it. “There are things about God that people cannot see—his eternal power and all that makes him God. But since the beginning of the world, those things have been easy for people to understand. They are made clear in what God has made” (Romans 1.20, ERV).

Our seminary professors taught us the theological term for this phenomenon. It’s called “natural revelation.” The Bible puts it like this, “The heavens tell about the glory of God. The skies announce what his hands have made” (Psalm 19.1 ERV). I used to think the Psalmist was just waxing poetic here, until I had the astounding experience of gazing at the stars on a clear night high in the Andes. Talk about a religious experience!

Of course, you can also hear God speak at ground level, and often through your fellow mortals. When a complete stranger performs an unselfish and unexpected kindness, or a friend sends a thoughtful message out of the blue just when you need it, or each time loved ones light the candles and sing Happy Birthday. Almighty God whispers whenever love, beauty and goodness are spoken.

I recall those tingly feelings hitting me all at once each time I got to hold our four babies for the first time. Natural revelation at its finest.

If you believe, as I do, that God made the heavens and the earth, then you know He designed it just as it is, for humankind to enjoy. What's more, He appointed us as the planet’s primary caretakers. So while you are here, take good care of this beautiful floating rock and enjoy it whenever you get the chance.

And get yourself ready for the next one. I hear it will be more beautiful yet.

Next time: It’s Friday! Let’s take a trip.