Heroes

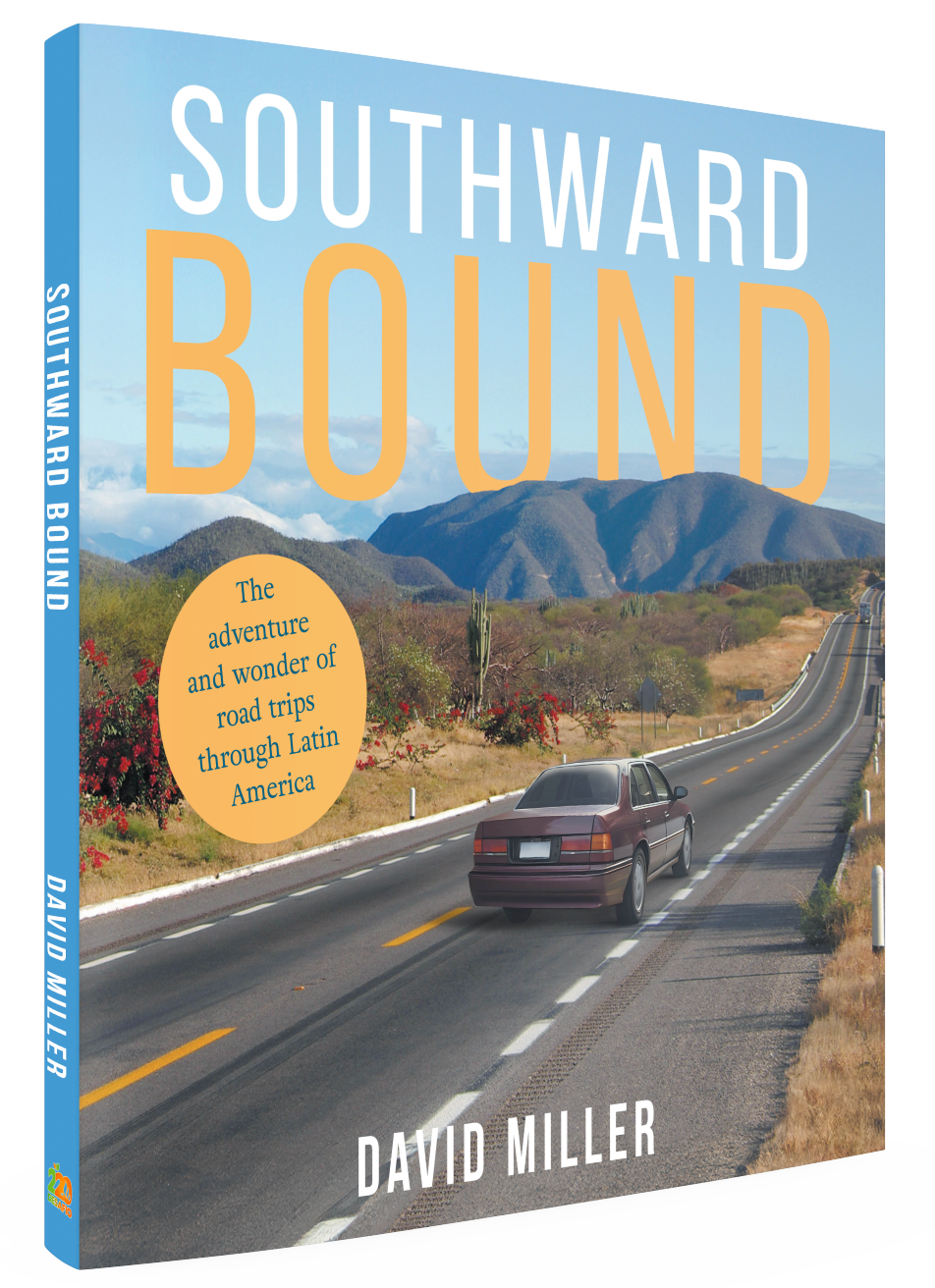

Thank you for your interest in my blog. It is now a chapter in my new book Southward Bound, The adventure and wonder of road trips through Latin America, available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com.

Thank you for your interest in my blog. It is now a chapter in my new book Southward Bound, The adventure and wonder of road trips through Latin America, available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com.

BTW, you can order the paperback book at 30% off the retail price from Ingramspark. Click here to go to the purchase site.

Thank you!

Dave Miller