Pura vida

There really is no other proper title you could put on a blog about Costa Rica. The phrase literally means “Pure Life” in English. Ticos, as the people of Costa Rica call themselves, use pura vida in everyday speech as a greeting or to express appreciation for something. Everyday life in this laid-back, user-friendly Central American country is best described as, well, pura vida.

There really is no other proper title you could put on a blog about Costa Rica. The phrase literally means “Pure Life” in English. Ticos, as the people of Costa Rica call themselves, use pura vida in everyday speech as a greeting or to express appreciation for something. Everyday life in this laid-back, user-friendly Central American country is best described as, well, pura vida.

Nicknamed the “Switzerland of Central America,” Costa Rica staunchly defends human rights and diligently maintains political neutrality. Despite its small size, the country of five million has earned world-wide respect. Ticos are justifiably proud of their personal freedoms, stable economy, solid educational system and history of peaceful solutions to political disputes.

Add to this scene of civic tranquility a lush, tropical landscape, and pleasant temperatures year-round (the climate of the capital, San Jose, is described as “eternal Springtime”). With its fascinating flora and fauna, and two seashores that provide abundant sport fishing, diving and surfing, Costa Rica sounds like paradise on earth. Okay, maybe not. But pura vida, for sure.

Costa Rica attracts a lot of foreign visitors, a fact illustrated as we were crossing the border from Nicaragua in our aged Camry. There we encountered a tall, sandy haired man in black riding clothes who told us he had ridden his motorcycle down from Alaska and was headed for Patagonia at the extreme southern tip of South America.

A black-clad, bearded cyclist was also crossing the border at that moment, pointed in the opposite direction. The man was from Argentina and told us he had started his trip in Patagonia, headed for Alaska. I thought it a noteworthy coincidence that the two bikers were crossing paths at the exact midpoint of the 13,000 mile ride.

The first place we headed once we cleared immigration was the beach. We considered it our duty to Ben and Molly, who had by now spent an entire month cooped up with Mom and Dad in our aged Camry. They deserved the chance to kick back and enjoy sunshine, salt air and warm surf for a couple days.

Costa Rica has an endless supply of beaches. Bounded by a 185-mile stretch of the Caribbean along its northeastern shoreline, 630 miles of warm Pacific Ocean on the opposite coast and just a few hours of travel time between them, the country offers more sand and surf per square mile than any place I know.

This is an informed opinion, by the way. Barbara and I spent a year in the early 1980s living in San Jose while studying at the Instituto de Lengua Española, a language school that trains Protestant missionaries destined for service in Latin America. Because we were newlyweds with no children and no other professional duty than to learn Spanish, we made it our quest to enjoy as many beaches as one can in a year’s time.

Many weekends found us on a bus headed to one or another coastal destination, from slow and steamy Puerto Viejo in the east to world-renown Manuel Antonio on the southwest coast. Of course, we made profitable advantage of the trips to learn Spanish, ahem.

Our favorite beach was Sámara in Guanacaste Province, and that was where we headed with Ben and Molly. The first time Barbara and I had visited Sámara, it was surrounded by cattle pastures whose fences nearly touched the sand. Thanks to Costa Rica’s attraction to foreigners, luxury condominiums and gated communities border the sand nowadays. Yet, Sámara manages to maintain its relaxing pace and laid-back charm.

You can still learn Spanish here, too. There are dozens of mom-and-pop language schools in town catering to foreigners. They will even put you up and feed you while you’re at it. We’re talking pura vida here.

Costa Rica was not always an enchanting place. In 1719, the colonial governor assigned to the region described it as "the poorest and most miserable Spanish colony in all America." His assessment was based largely on the absence of gold and silver, resources of primary interest to Europeans of the time.

The country did possess a rich natural resource that would prove to be a gold mine in later years. The fertile soil on Costa Rica’s well-watered mountainsides is some of the best in the world for growing coffee. First planted in 1808, it soon surpassed tobacco, sugar, and cacao as Costa Rica's primary export and remained its principal source of wealth well into the 20th century.

Ticos carry on a friendly rivalry with Colombians as to which of them produces the best beans. The competition has inspired a clever jest about Juan Valdez, the poncho-clad coffee farmer whose image, standing alongside his burro, has become Colombia’s official icon for promoting its coffee as the world’s best.

“Ah, but haven’t you heard?” Ticos say with a wink. “Juan Valdez drinks coffee from Costa Rica.”

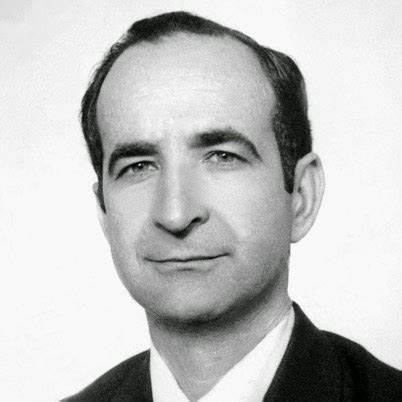

Costa Ricans credit one man more than any other for their country’s modern success. José María Hipólito Figueres Ferrer, known to his countrymen by his nickname “Pepe”, could be called the nation’s George Washington and Abraham Lincoln rolled into one.

Pepe Figueres was born into the family of a country doctor in 1906. At age 18 he left for Boston to study hydroelectric engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, returning four years later to become, you guessed it, a coffee farmer.

He turned his plantation into a laboratory for egalitarian practices. Figueres built suitable housing and recreational facilities for his workers, and provided medical care for them. A community garden and dairy supplied families with free vegetables and milk.

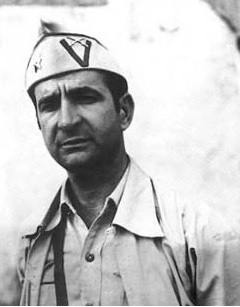

Around the time of WWII, tensions between rival political parties threatened to destroy Costa Rican democracy. Figueres responded by training the Caribbean Legion, a militia force of 700. In 1948, he launched a revolution along with other landowners and student agitators. In the bitter, 44-day struggle, the rebels defeated a coalition of army troops and communist guerrillas to unseat the government.

This all-too-familiar scenario produced quite unprecedented results. The victors formed a provisional junta over which Figueres presided. The junta immediately abolished Costa Rica’s standing army, granted voting rights to women and persons of color, and oversaw the drafting of a new constitution by a democratically elected assembly. Once the reforms were in place, the junta resigned and yielded power to duly elected president, Otilio Ulate.

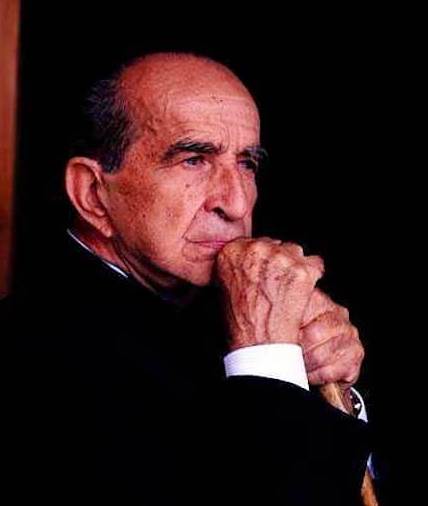

His countrymen, impressed by his bold action and impeccable integrity, elected Pepe Figueres president in 1953 and again in 1970. His three terms at the helm of government produced more democratic reforms and fostered steady prosperity. Ticos like to mention, with thinly disguised pride, that their country has more teachers than policemen. The modest boast reveals something striking about the legacy of Pepe Figueres.

Figueres enhanced his legacy yet further by correcting a historic wrong. In the 1870s and ‘80s, Costa Rica brought thousands of Jamaicans to build a railroad from San José to the Caribbean port of Limón. Officials considered the immigrants, who were of African descent, better suited than native Ticos to work in the steamy jungles of the coast.

As often happens with immigrants, Jamaicans worked for lower wages than the locals. Many died from disease and accident. Unfortunately, their sacrifices did not earn them equivalent gratitude and respect. Afro-Caribbeans and their descendants could not reside outside the province of Limón. Laws prohibited them from even traveling to the rest of the country and mingling with whites.

Pepe Figueres and his fellow revolutionaries ended this deplorable policy in 1949. They saw to it that Costa Rica’s new constitution granted full rights of citizenship to all persons of African descent.

Many of the Jamaican immigrants who built the railroad were evangelical Christians who planted scores of churches on the northeast coast and along the railroad line. One of their descendants, Pastora Irma, is a friend of ours.

She doesn’t talk about it much, but Pastora Irma led a hard life before she found Jesus. Her demeanor is serious, almost stern, hinting at the abuse and violence she witnessed, or perhaps experienced, in her pre-Christian days. Irma comes across as a no-nonsense, street-smart lady who tolerates no fools.

But under that tough exterior beats a heart that loves people, particularly lost people who have yet to find God. Not content to win souls in her downtown parish only, she planted several more churches in and around the city of Limon. The congregations are populated with ex-drug addicts, former sex workers, recovering alcoholics and other persons who, like Pastora Irma, led a hard life before meeting Jesus.

Once it fell to Barbara and me to organize a staff retreat in Costa Rica for missionaries serving in Latin America. We made sure that our schedule permitted us to worship on a Sunday morning in Pastora Irma’s church. She greeted our group shyly, suggesting that one of us should preach that morning. She felt it was proper protocol to invite visiting missionaries into her pulpit.

“No way,” I said, with a wink at my colleagues. “We are all on vacation today.”

We had agreed beforehand to decline an invitation to preach, and it was absolutely the right call. As soon as Pastora Irma mounted the platform to help lead the lively hymns favored by persons of African descent, the serious demeanor fell away and she was caught up in enthusiastic, joy-of-the-Lord praise.

Pastora Irma preached that morning on the resurrection. She delivered a comprehensive, high-energy narration of Jesus’ triumph over death, what it accomplished for His followers then, and what it promises for His followers today. It was a memorable meeting.

The meeting was about to become even more memorable. Near the end of the service, an usher called me to the back of the chapel to pray for a woman who had suddenly fallen unconscious. One of our missionary colleagues, a doctor, could not revive her and ordered that she be taken to the hospital. Sadly, she was dead on arrival.

We received this news over lunch with Pastora Irma and her congregation in the church basement. The dead woman, a single mother of two in her late 30s, had suffered a massive heart attack. The tragedy left us understandably shocked and shaken.

None were more shaken than Pastora Irma. She explained to us that the young mother had used drugs and alcohol for much of her life. The abuse likely wore her heart down to the point that it simply stopped beating.

“She gave her life to Jesus just last year,” Irma said. “I baptized her in January.”

We all fell silent as we contemplated the scenario. A young woman leading a hard life of abuse and violence finds Jesus through Pastora Irma. As a result, that young woman is now walking on streets of gold.

“I want to compliment you on the moving sermon you preached this morning on the resurrection,” I said to Pastora Irma. “But this young woman’s story, well it’s just a remarkable case study in the resurrection."

“It is a tragedy, of course, that she left behind two young sons,” I conceded. “But think of how much more tragic it would be had she not found Jesus.”

Life, and death, happens to everybody. Sooner or later, every one of us must come to grips with dying. Jesus’ words, quoted by Pastora Irma in her message that Sunday, puts the issue in very clear terms.

“I am the resurrection and the life. The one who believes in me will live, even though they die; and whoever lives by believing in me will never die” (John 11.25-26, NIV).

What do you think? Isn’t this simply pura vida at its best?

Thank you for your interest in my blog. It is now a chapter in my new book Southward Bound, The adventure and wonder of road trips through Latin America, available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com.

BTW, you can order the paperback book at 30% off the retail price from Ingramspark. Click here to go to the purchase site.

Thank you!

Dave Miller