Where there is no bridge

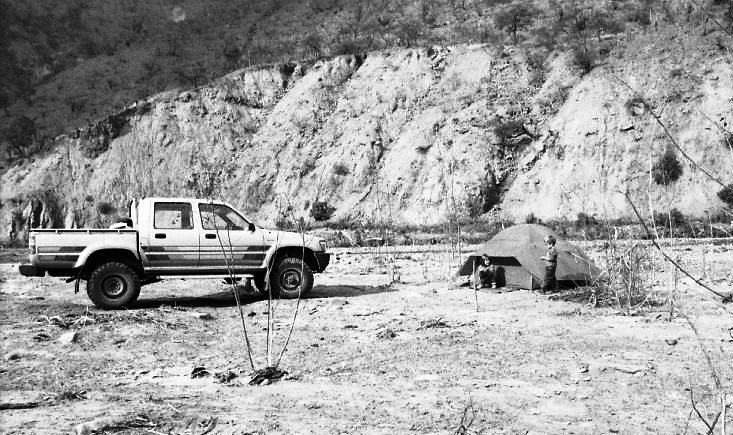

A major reason you drive a four-wheel vehicle when stalking trout in the Andes is to get through the rivers that lay between you and your favorite fishing holes. Not all of them have bridges.

This is generally not a problem in high elevations, because for much of the year the rivers don’t run full and the water level at the fords rarely comes up to axle height. The danger to you and your passengers is minimal.

But come rainy season, heavy downpours will make you think twice before taking the plunge. In such circumstances you must strictly follow three rules.

1. Check the water level and current.

2. Be sure to engage the four-wheel drive.

3. Take it slow and do not stop.

Let’s take them one at a time. Theoretically, you can cross any water that does not enter the air intake to your engine. Except, of course, white water. Then you best not get yourself into anything over tire height or you could be swept away. One of the saddest sights along our river banks after flood waters have receded is a nice, new SUV half-buried in sludge.

If you can’t eyeball the depth from shore, you better climb out and wade into it. Or better yet, ask a passenger to climb out and do the wading.

Second, you have a better chance of making it across if all four wheels propel your vehicle. It’s embarrassing to stall in the middle of a river when you’ve run out of traction. Been there, done that. If backing out is not an option, and often it is not, the only thing you can do is to ask your passengers to climb out and push.

Finally, do not speed across rivers. Leave that to motor boats and dragonflies. Your need the rubber to meet the river bottom and stay there. Literally, slow and steady wins the race.

One time, four of us were coming home from a mediocre day stalking trout in the rainy season. About twilight, we came to the last river ford between us and home. A Quechua family was parked on the bank in a minivan with no license plate. This indicated that they had purchased the vehicle from smugglers. An unlicensed teenager was at the wheel. We assumed he was unlicensed because people who drive contraband minivans don’t usually bother with drivers licenses.

We checked the water level, not quite tire height. The current was strong but not overpowering. We could do this. I engaged the 4-wheel, slipped into low-range and accelerated just above idle. It was a piece of cake.

When I got out to inspect the tires, the teenager at the wheel of the minivan was watching intently. I waved at him to come on over. “But take it slow!” I shouted. “Slow and steady wins the race!”

Instead, the kid revved his engine to jet speed and popped the clutch. The minivan did a swan dive into the river, lurched out to the middle and stalled in a cloud of steam.

The four of us looked at each other, then reluctantly waded in to help push. The minivan would not budge. After several futile attempts, we thought to ask the kid to try and restart the motor. It sprang to life instantly. “Okay,” we said, “we’ll push and you drive it out.” He revved the motor, popped the clutch and once more stalled in a cloud of steam.

That was when Steve happened to look inside the cab and notice that the parking break was set. It confirmed what we had suspected all along: this kid had not passed Driver’s Ed.

“Okay,” we said, “release the brake, we’ll push and you drive it out. This time, it was a piece of cake.

The bizarre affair taught us a new rule we had never thought of before:

4. Do not attempt to cross a river with the parking brake set.

Should you ever find yourself crossing a river in the jungle, be sure you strictly follow all these rules.

Several Quechua brothers and my two kids, Sarah, 9, and Ben, 6, once joined me on a preaching trip to Isinuta. This settlement sat literally at the end of the road in the Chapare region, a lush, steamy jungle at the base of the mountains. The Chapare is ideal for growing bananas and coca leaf, the raw material for making cocaine. Yes, you heard right, cocaine. No place on earth needs preachers more than the Chapare.

Crossing the gentle river into Isinuta on Saturday afternoon was downright pleasant. We had sunny skies and a cool breeze, unusual weather for the Chapare. That night it changed with a vengeance. Rain fell in torrents from midnight until 11 a.m.

We started for home after Sunday lunch but got only as far as the river, which had morphed into a brown, boiling torrent. A dozen flatbed trucks lined the opposite bank. They had been headed for Isinuta to take on cargo, but the high water stopped them. Now a steady stream of dugout canoes were ferrying hundred-pound bales of coca leaf across the boiling torrent to be loaded on the trucks.

In accordance with Rule 1, brother Felix shucked down to his undies and waded to the middle of the river to check the water level. It came to his armpits. He calculated that if it receded to his waist, we could cross. So we waited, and waited.

Sarah and Ben amused themselves playing on the beach among the bamboo groves. The Quechua brothers caught up on sleep, having stayed up all night preaching. I waited, little knots forming in my stomach as the afternoon wore on.

About an hour before sundown, Felix waded once again to the middle of the river. The water had receded, but only to mid-stomach. That was when I hinted to the kids that we might be spending another night in the Chapare.

“But, Daddy, we can’t do that!” they protested in unison. “We have to get home tonight! Mom will worry.”

Tears started to come. About then another dugout canoe laden with bales of coca leaf pushed off from the bank. I did not relish the idea of the kids and I spending the night in this company.

“All right,” I assured them. “Don’t you worry, we will make it across.”

How on earth that would happen I did not know. The little knots in my tummy got tighter.

About then a tall stranger came by, looked at me with a strange twinkle in his eye and said, “You’re the missionary, right?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Trying to get across this river, are you?”

“Yes, I am.”

“Well, just trust God,” he said cheerfully. “He will see that you get across.”

“Thank you, sir.” I forced a weak smile.

He started to walk away, then paused.

“But one thing, you must remember,” he said, still cheerfully. “God does not help sinners. If you have sin in your life, you won’t make it. You will get stuck in the river.”

He winked, turned around and disappeared. I never saw him again.

In fact, I did not see where he went once he left. It was like he disappeared into thin air, or ascended into the clouds. Maybe he simply walked across the water. I don’t know.

I do know that, added to the worry of getting my pickup across the river, I now faced enormous shame if I failed. The entire Chapare would know that the visiting missionary was really a sinner who could not count on God’s help in a jam.

Just after dusk we decided it was now or never. I climbed in behind the wheel and turned on the headlights. I was alone in the cab. I had sent Sarah and Ben across the river in a canoe with Felix. I did not want to have to pull them out through a window when I stalled in midstream. The rest of the brothers climbed up into the truck bed so they could jump out once I stalled.

I locked the truck in 4-wheel drive, slipped into low gear and gently eased over the bank. The headlights disappeared. The water had come up even with the hood. The brothers in the truck bed told me later the water came within a couple inches of the rim, causing them to consider jumping out early. I kept light pressure on the accelerator, fighting the urge to race across the boiling brown water. I prayed silently, fervently, desperately. Slow and steady, slow … and … stea … dy…

Somehow the truck kept going. After a bit, my headlights reappeared. Soon after that, I heard the delicious sound of water running off the fenders. Then we were on the beach. Only when I got out to check the tires did I notice the eyes of every trucker on the bank above staring at me, every mouth open. “You looked like a big catfish coming out of that water,” one of them said. “We didn’t think you would make it.”

Guess what.

That was the moment my suspicions about the tall stranger were confirmed. He was indeed an angel. Whether supernatural or not was beside the point because, like all angels, he delivered a timely message at a critical moment. He assured me that God was really the One who got us across the river. What a thrill!

My anxiety about being exposed as a sinner also eased then. What a relief!

As you know, God has people do some pretty outrageous stuff sometimes.

“Moses, get this Israelite horde across the Red Sea. Now, Moses!”

“My dear boy, go kill that giant. Use your slingshot.”

“Mary, you are a fine young woman with a spotless reputation. I want you to have my baby.”

The exploits of these folks are extraordinary when compared to the things God asks of you and me. But don’t forget they were just ordinary folks, like you and me. Do you suppose they got knots in their stomachs? Did they wonder how on earth God was going to make this thing happen? Do you think they maybe even had second thoughts about obeying His outrageous demands?

I kind of think they did. Of course, the uncertainty and fear of failure did not stop them. Despite knotted stomachs and second thoughts, they took the plunge.

That’s why they are in the Bible, along with a lot of other ordinary folks just like you and me.

Next time: El dorado