No joke

Did you hear the one about the three guys from Florida, Arkansas and Texas comparing the size of largemouth bass in their home states?

“In Florida, we don’t keep anything smaller than this,” the first guy says, stretching his hands two feet apart.

The Arkansan stretches his hands three feet apart. “Well we don’t keep anything unless it’s this big,” he says.

The Texan says nothing.

“What about Texas?” they finally ask.

“Ah well, we keep a fish if it’s this big,” he says, stretching his hands eight inches apart.

The other two hoot and holler. “That’s a disgrace!” they sneer. “We hear that everything’s bigger in Texas. But obviously not the fish, ha, ha, ha!”

“A course,” the Texan drawls, “the only way we ever measure ‘em is between the eyes.”

Jokes are essential gear for fishing. They counter boredom when the fish are not biting and lift spirits on the way home after getting skunked.

In the Andes, humor is particularly helpful when you confront a sudden, brutal storm or a road-blocking landslide. At those moments, a good story teller is as indispensable as a waterproof jacket or a thermos of hot coffee. I suggest you always include someone with a well-developed sense of humor in your circle of fishing buddies.

This was how our trio of fishermen used to share chores when stalking the wily Andes trout. Because I owned a reliable four-wheel-drive, I did the driving. Jorge, a native Bolivian bred to the land, guided us over obscure mountain roads to hidden lakes. Daniel kept an inexhaustible supply of jokes at ready to handle the humor duties.

I wish I could recall Daniel’s jokes, but confess that I couldn’t even understand most of them. Both Jorge and Daniel were native Spanish speakers, which I am not, and could appreciate the nuances of the language, which is indispensable in order to understand punch lines.

What’s more, Daniel would tell many of his jokes while feigning a speech impediment. This rendered the punch lines yet more hilarious, I gathered, by the way Jorge hooted and hollered at the end of each joke. I would sit there behind the wheel, a silly grin on my face, feigning hilarity. Suddenly Jorge would say “Ay, Daveed, you didn’t get it, did you?!” And then both Daniel and Jorge would hoot and holler even louder.

This reaction never offended me because they never laughed with malice. Rather, it was a kind of jovial appreciation, like their clueless gringo friend was helping make the joke funnier. Usually, in fact, the three of us would end up laughing hilariously together--at me.

Daniel was from Nicaragua, where he grew up in an affluent family of coffee planters. In the 1970s he was on his way overland to Brazil to study medicine. He made it as far as Bolivia when the door to that plan unexpectedly closed. Friends prevailed on him to enroll instead in Cochabamba’s San Simon University. There he met Jenny, the love of his life, and after graduation settled down to raise a family.

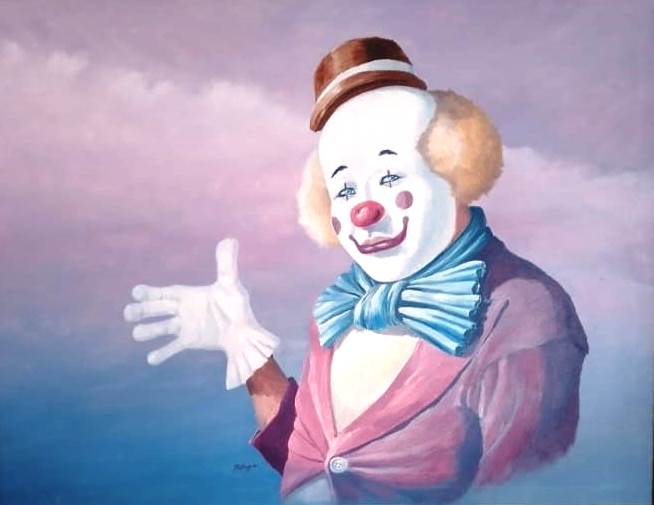

I met Daniel playing fast-pitch softball. Teammates had given him the nickname “Nica” because of his country of origin and standout knowledge of the game. His standout sense of humor had already earned him a reputation as a fun-loving clown.

That is not my own assessment, it’s actually enshrined in art. Daniel once commissioned Jaime, the pitcher on our softball team and professional artist, to paint his portrait. Jaime asked what sort of pose Daniel preferred. “Whatever you think fits me,” he said.

Daniel liked the result so much that he hung Jaime’s painting inside the front door of his home. As you enter, you are met by a circus clown, hands outstretched as if about to perform a magic stunt. Despite the thick makeup and fake nose, anybody immediately recognizes the man with the mischievous gleam in his eye behind the impish grin. Jaime’s masterpiece captured Daniel’s personality spot on.

I ought to correct any insinuation that Daniel was just a funny guy. Actually he was an eminently successful physician with not one, but two, specialties. He would leave home every day at 5:30 a.m. to attend couples at a fertility clinic, helping bring scores of healthy babies into our fair city every year.

Afterward, he crossed town to the university hospital where he practiced his real passion: nuclear medicine. Daniel was one of just two doctors with this specialty in Bolivia when he founded the Center for Nuclear Medicine at San Simon, introducing patients and their attending physicians to radiopharmaceutical diagnoses and radiation therapy.

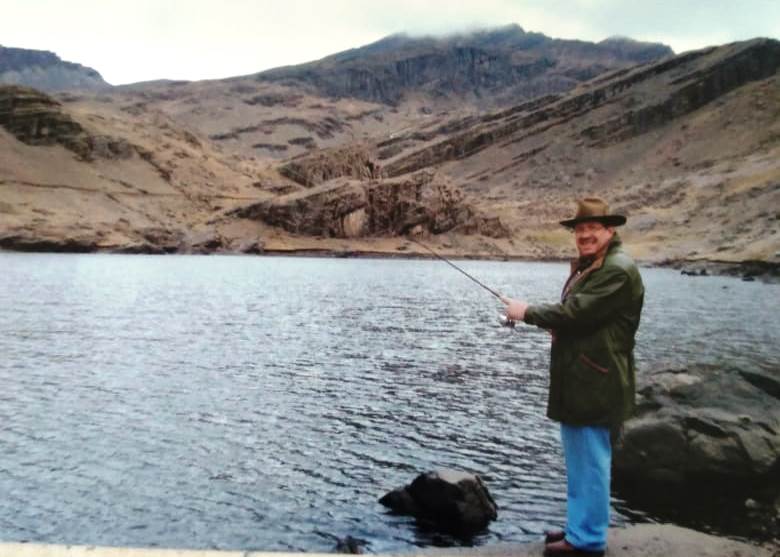

Daniel was humble as well as humorous, so few of us knew this about him. And several softball seasons would pass before I learned of his passion for stalking the wily Andes trout. We started fishing together and kept it up long after either of us could swing a bat.

Even though we went fishing every chance we got, it turned out to be not nearly enough, because Daniel got cancer.

It started as a stomach ache, was diagnosed originally as gastritis, and finally discovered to be colon cancer. Like all cancers, it hit Daniel at the worst possible time. He was at the top of his game as a physician. His two sons had recently graduated college and launched careers. His daughter had given birth to his and Jenny’s first grandchild. The family needed him and Daniel craved time with the family.

The cancer was aggressive. Within weeks, he could no longer work. He moved with Jenny to Buenos Aires for several months of treatments, but that did little to slow the malignancy. When they returned home, Daniel prepared to die.

I know this reads like a grim and depressing story, and of course it was. Onliest thing, I don’t remember ever feeling grim and depressed when I hung out with Daniel during his illness. You walked in the door and he greeted you with the same mischievous smile as the clown on the wall. Jenny fussed about, serving you a tasty snack. They both seemed more interested in what was going on with you than with them.

Once or twice I asked Daniel how he felt about, um, the future, declining to speak the “D” word. His answer was consistently the same. “My life is in God’s hands. If this is what He has for me, no worries. I trust Him completely.”

I can remember the afternoon on the softball diamond when Daniel put his trust in God. A group of Major League Baseball players had come to Cochabamba during their off-season to give our guys some pointers on the game. Afterward, they talked about following Jesus and invited anyone who wanted to, to follow Him as well.

Daniel was one of those who did. I dropped by his house a few days later to talk about his decision. “I have known about God since my mother took me to church as a kid,” he told me. “But now I know God, for real. I have peace like never before.”

He never looked back. Years later with death staring him in the face, Daniel radiated a calm, gracious serenity. Near the end, I visited him at the hospital. He was frail and trembling, a shadow of the vigorous sportsman he had been his whole life. To manage the pain, he spoke in short, direct sentences between long, heavy breaths. The pain was beyond intense, yet he did not once complain. Rather, he smiled, a lot.

The scene reminded me of what Hebrews 12:2 says about Jesus, “who for the joy set before him, endured the cross, scorning its shame.” Like Jesus, Daniel never surrendered his joy.

I think too many times we let our veneration for Jesus obscure his standout sense of humor. He told some funny jokes, all of them with famously memorable punch lines.

Like, “Tell me, Sir, how can you possibly see a speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye when there’s a 16-foot, 4 by 12 sticking out of your own?”

“You law professors are a real case, you know that? You carefully strain tiny bugs out of your lemonade, then turn around and swallow a whole, hairy camel, hump and all!”

LOL.

The jests continued even after His resurrection. Do you recall the trick he pulled on Peter and the five other disciples who go fishing on Lake Galilee? They spend an entire night getting skunked. When the sun comes up, Jesus appears on shore and hints that they have been fishing the wrong side of the boat. Yeah, right. Nevertheless, they cast their net over there and immediately limit out, big time.

Realizing it is Jesus, Peter plunges into the water and clamors ashore, leaving his buddies to drag the boat and overstuffed net to the beach. Once there, the soaked and sweaty fishermen find Jesus grilling fish for their breakfast. What a cheery morning it’s turning out to be.

Can’t you just picture them relaxing around the camp fire, grinning and happy, trading stories and saying stuff like, “You know, guys, it just doesn’t get any better than this.”

Well, in fact it does get better.

A few hours after my afternoon visit to his hospital room, Daniel spoke one last time by phone with his daughter in New York, then slipped into a coma. Early next morning, with Jenny and his two sons at his bedside, Daniel took his last breath.

I had the honor of delivering the eulogy at Daniel’s burial. It was perhaps the least demanding assignment of my entire preaching career. I had only to talk about a life well-lived and a race well-run all the way to the finish. In Daniel’s case, that was easy to do.

Afterward we lined up to toss dirt clods into the open grave. Jorge sidled up beside me and opened his outstretched hand, a spinner bait cradled in the palm. He winked at me and the two of us tossed the fishing lure onto the casket.

A titter of laughter rippled through the crowd of onlookers as people who knew about Daniel’s passion for fishing understood the meaning of our final tribute.

At that moment, I was certain I heard Daniel laughing as well.

No joke.

Next time: Mastering the fundamentals