Home in the Llajta

A plaque on our wall says, “Home is where you hang your heart.” In four decades of marriage, Barbara and I have made our home in Kentucky, Costa Rica, Bolivia, Florida, and Indiana. But the place where we have hung our hearts the longest is Cochabamba.

The Epic Journey ended in Cochabamba 89 days, 12,634 miles and 12 border crossings after we departed Indianapolis. Our bus ride through the Argentine Chaco brought us to the banks of the Pilcomayo River. We crossed in a motorboat to Bermejo, Bolivia, and presented our papers at the immigration office. Ben confessed that he was feeling a bit nervous, unsure of how it would go for him and Molly because they were Bolivian citizens traveling on U.S. passports. He also fretted that the authorities might hassle him over his draft status, since he had not served the mandatory year in the army required of all young Bolivian men.

“However, the most honest and efficient border official I´ve ever met stamped us in, no worries, and welcomed us home,” Ben wrote in his journal. “I can’t lie, it was an emotional moment.”

From Bermejo we traveled in a shuttle van to the city of Tarija. We swerved and skidded on the winding highway for the entire four hours in order to dodge mounted vaqueros and the cattle herds they were driving to summer pasture. By then, I confess that I was a bit nervous. First thing next morning, I splurged on air tickets to Cochabamba. I decided that a one-hour flight in lieu of another 20-hour bus ride was just the way to celebrate the last leg of the Epic and, I can’t lie, make it home in one piece.

“Cochabamba” [Koh-cha-BAHM-ba] is a compound Quechua name meaning “the flat place with water.” Its 16th century founders located the city inside a gentle bend of the River Rocha near a marshy lake, thus ensuring a constant water supply. Cochabamba natives fondly use another Quechua word for the city which you won’t find on maps. “Llajta” [YAHK-tah] loosely translated can mean “town” or “people” or even “my people.” To those of us lucky enough to live here, the Llajta is simply “the home town.”

The evening our flight landed in the Llajta, the home town soccer team faced off against a menacing rival in a do-or-die playoff match. Ben remembers it like this.

Felix Capriles Stadium was bursting at the seams, everybody cheering for our club, Wilsterman. We rushed to the stadium in time to catch the second half. Games here are dramatic and this one did not fail to impress. Lindsey was crushed under several youths trying to catch a gift ball kicked into the stands. A player from the rival team was knocked to the ground by a bottle thrown from the bleachers. A young man punched the main referee in the face, then managed to wiggle free of riot police and escape into the mass of fans. The local side pulled through with an impressive goal to win and we made a mad dash to the exit before 30,000 celebrating Cochabambinos poured out into the streets.

I’m still in a state of shock, it doesn't quite feel real. Because we have been in transit for the last three months, the idea of permanence seems unnatural. But before getting lost in the excitement, I would like to pen some words of closure to the journey.

No words could describe the deep GRATITUDE I feel for the places we encountered, and for those who hosted us, interacted with us, and opened up their hearts, homes and refrigerators. They taught many a lesson about hospitality. I’m still humbled by the people who vacated their bedrooms so we could occupy them, covered extra shifts at their workplace to show us around and refused gas money.

For myself, I experienced similar feelings, but expressed them differently. For days, I went around humming the old Simon and Garfunkel tune, “Gee, but it’s great to be back home! Home is where I wanna be-ye . . .”

We didn’t have an actual home to come home to. Before leaving for the States a year and a half earlier, Barbara and I had moved out of our rented apartment and warehoused all our belongings. No worries, our good friends Paul and Kattia Jones were away on furlough and loaned us their spacious home until we could relocate. We arrived just days before Christmas, so our good friends Graham and Lori Porter graciously hosted us for the holidays, stuffing us with scrumptious food and letting us take long naps on the sofa between meals.

Did I mention that good friends are what make the Llajta, well, the Llajta?

Cochabamba sits in a wide valley 8,500 feet above sea level, which at this latitude gives it a climate much like California. It supports palm trees and pine trees equally well and has only two annual seasons: wet and dry. Intermittent rains fall between December and May, none fall during the rest of the year. The most constant element of the weather is golden sunshine.

California gets its rain during the winter, but because seasons are reversed, Cochabamba’s rain falls in the summer. It’s a subtle but important difference that means our weather is neither as cool nor as hot as California’s. Daytime temperatures range between the low 70s in winter and the high 70s in summer. Like other cities located in high Andes valleys--Medellin, Cuenca, Cusco, Salta--the climate in the Llajta is described as “Eternal Spring.”

It may sound too good to be true, but it is. Sometimes Barbara and I, while strolling through a shady park or sitting on our veranda, will look at one another and say, “You know, on a day like this, why would you ever think of living anywhere else?”

Few tourists come to Bolivia and fewer come to Cochabamba. The Llajta offers no must-see attractions like Lake Titicaca, or Tiawanaku or the Uyuni Salt Flats, sites several hours distant. The shortage of tourists does not bother locals, however, who quip that Cochabamba is a great place to live but you wouldn’t want to have to visit here.

Barbara and I were barely beyond our honeymoon when we first arrived in Cochabamba. Our three eldest children, Sarah, Benjamin and Molly were born in San Pedro Clinic when it was little more than a stately home with delivery rooms and a nursery. We raised the kids their first years across the street from Felix Capriles Stadium, which probably infected them with soccer fever. Carmen, our youngest, joined the family when we were furloughing in the U.S. She is the only one of us with blue eyes. This sometimes puzzles Bolivians until we explain, tongue in cheek, that it is because she was born in the middle of a cold Indiana winter.

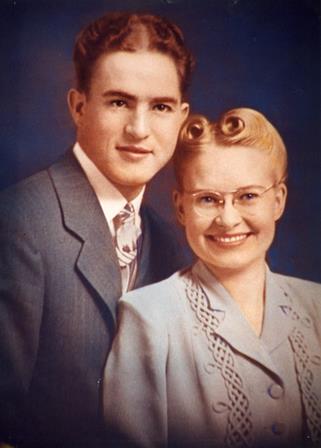

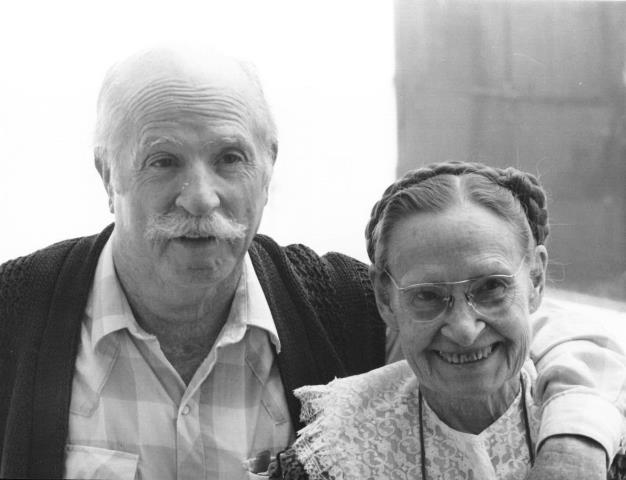

Lest I create the impression that we settled in Cochabamba because of its ideal climate, stunning natural beauty and engaging lifestyle, I should mention that our missionary agency sent Barbara and I here to replace Dr. Homer and Elvira Firestone, who were about to retire. We were chosen for the assignment, we later learned, largely because we were young and healthy and therefore expected to endure the rigors of the Andes. Right off the bat we learned that whatever our other credentials, we would never be able to fill the Firestones’ shoes.

Homer grew up in the Oklahoma Dust Bowl and trained as a Navy pilot in WW2. He earned a Ph.D. in Anthropology and conducted pioneer research on Bolivia’s aboriginal languages. Elvira used her B.S. degree in Nursing to deliver babies and treat illnesses for country folk who seldom saw a doctor. When the couple became “tentmakers” [missionaries who support themselves through self-employment], she opened Bolivia’s first-ever Chiropractic clinic.

Homer and Elvira had been working in Bolivia nearly 40 years by the time Barbara and I arrived. We had the good fortune to spend our first year with them, soaking up their wisdom. Homer tutored us on his methods for growing successful Jesus movements among Quechua- and Aymara-speaking campesinos [Native American peasant farmers]. His simple, three-step strategy produces extraordinary results if correctly applied.

Step One: Show up. “Don’t forget,” Homer constantly reminded us, “ninety percent of the job is just showing up.” Simple as it sounds, showing up to remote villages in the high Andes or dense Amazon jungle presents some challenges. Travel often meant hours of bouncing over precarious mountain roads, then more hours trekking over rugged trails. The risk of coming down with sorojchi [altitude sickness] or ingesting parasites was constant. But an opportunity to present the gospel to campesinos hungry to know God always made showing up worthwhile.

Step two: Don't plan. “Plans always change, so why make them in the first place?” Homer pointed out. “Besides, God already has a plan and it’s far better than anything we could come up with. Best look for God’s plan and follow it.” The usefulness of this advice when operating in a foreign culture should be obvious, especially to those of us who live by faith and not by sight. But not so. I once gave a four-hour lecture to a university Missions class on Homer’s strategy. When I finished, the professor pointedly reminded the students that their term projects entitled “My Five-year Plan” would be due the following week. Needless to say, I was not invited back.

Step three: Don't mess it up. This is by far the most difficult of the three to put into practice and the one that creates the ugliest disasters when not strictly followed. I could tell you story after story of well-meaning outsiders who decided that the natives were doing things all wrong and needed correction. But I won’t, because I suspect you know plenty of your own stories. To paraphrase the old saying: Oh, what a tangled mess we mix, when we apply a foreign fix.

We tried our best to follow the Firestones’ guidelines because the strategy had obviously worked for them. Homer and Elvira managed to launch not one but two exceptionally successful church movements during their career in Bolivia. The first eventually outgrew its parent denomination in the U.S. Not bad for showing up with no plan.

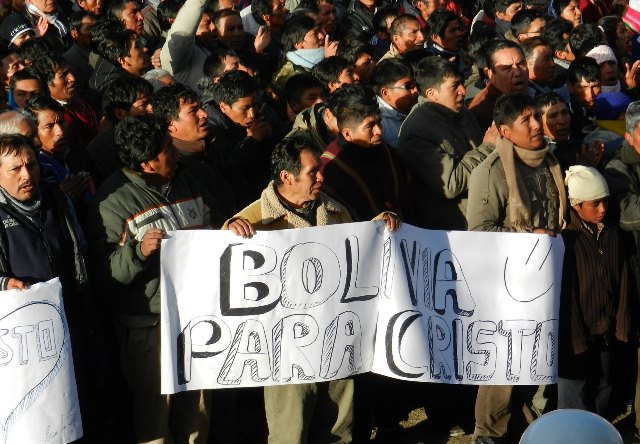

By the time Barbara and I showed up, the second movement that the Firestones launched had become the largest and fastest growing church affiliated with our denomination in Latin America. Over the next two decades, we watched la Iglesia de Dios Reformada triple in size. Accurate statistics were difficult to collect, but a fair guesstimate would be 12 to 15 thousand baptisms and approximately 160 new congregations planted. Understand, I conducted a relative handful of the baptisms and Barbara and I did not plant one single church. We had our hands full just trying to keep up with our Bolivian coworkers.

Florencio Colque was one of those coworkers. He was, like all leaders in the Bolivian church, a tentmaker. Weekdays he operated bulldozers and road graders for the Highway Department to support his family. Weekends, he showed up at juntas [HOON-tahs, rural camp meetings that feature all-day music and Bible teaching] to present the gospel. One of the most intelligent men I have ever known, Florencio spoke three languages fluently although he never made it past the second grade.

We spent a good deal of time together traveling to juntas and I often heard Florencio present the gospel a la boliviana. I remember one sermon in particular.

“We learned from our grandfathers to walk a certain road,” he told the assembled campesinos. “They told us 'You must worship this rock, this spring, this mountain peak.' When we asked them why this was, they said, 'Because this is the teaching we received from our grandfathers.'

"Then, humble men came to us with the gospel and spoke to us in a way that we could understand and believe. Now we have come out of darkness. Now we have entered the light. Now we worship God in spirit and in truth."

This stuck with me because I believe it explains the essence of why Andean peoples are coming to Jesus in great numbers. It has to do with freedom from fear.

Fear incited the persecution of the earliest Christian believers in the Andes. For instance, when Florencio and his family first turned to Jesus, their neighbors beat them up and threatened to kill them if they did not return to the old religion. This was because the rituals they inherited from their grandfathers were designed to appease the demons and pay homage to the gods of nature. Failure to perform these rites invited severe punishments. The village might suffer a plague, or the crops would fail, or the livestock would stop reproducing.

I once witnessed up close and personal the interplay between fear and freedom and I remember it as if it were yesterday. A middle-aged campesino, I will call him Pedro, came up to me one day at a junta and told me he had just been baptized. I congratulated him for it.

“Now I need to clean my house,” Pedro said earnestly, “and I want your help.”

No one had ever made this sort of request before. I thought it kind of odd and was inclined to brush it off. But Tomas and Felix, two of our Bolivian coworkers, were standing nearby and overheard the conversation. They nodded their heads as if understanding perfectly what Pedro wanted and agreed to help him.

“What’s this about?” I asked Tomas. “What does he want us to do?”

“It’s kind of hard to explain,” he said, “but you’ll see.”

So on the appointed day we showed up at Pedro’s village with no plan and me wondering what kind of mess I had gotten myself into. The place was typical of Andes farm communities, scattered adobe houses adorned with talismans fixed like lightning rods on the rooftops. These are Ojos de Dios [Eyes of God] and serve to ward off evil spirits. The homeowners likely had buried dried llama fetuses under their front doors, as well, a common custom to gain favor with the goddess of the earth.

A beaming Pedro met us and led the way to the side of his house. He explained that when he built the place he had buried a Devil’s Banquet in the adobe wall as protection against wandering demons. Should one pass by when hungry and not find anything to eat, he might get angry and exact revenge.

The Devil’s Banquet symbolized the apprehension that Pedro had lived with every day before he met Jesus. But now he was no longer intimidated by demons and devils and he wanted to be rid of this symbol of the old fear. He handed us a pick and shovel and pointed out where to start digging.

I half expected Tomas and Felix to lead us in a serious ceremony before uncovering the Devil’s Banquet, something akin to those shadowy scenes in Hollywood movies with spooky background music meant to break the spell of ancient gods. But nothing doing. The two were cracking jokes as they attacked the wall.

In minutes they had pried the banquet out of the adobe and I got my first look at the thing. It consisted of a three-foot length of log, hollowed out and with a lid cut into one side. We lifted that off and peered at the hard candies, ears of corn, communion wafers and other stale edibles packed inside.

“Look here, these demons didn’t eat a thing!” Tomas snickered. “And no wonder, this stuff is garbage. You really expect a self-respecting demon to eat this junk?”

Pedro looked puzzled. His banquet offered pretty much the standard fare because he had purchased it from certified witches who knew the correct ingredients.

Felix clasped a hand on his shoulder and winked. “Brother, if you wanna pacify the Devil, you had better provide some better eats. Otherwise, don’t bother!”

Pedro smiled sheepishly and joined in the mirth. It turned out to be one of the funniest house cleanings I have ever been party to.

After some refreshments, we said goodbye to Pedro, carried off the hollow log and made us a bonfire on the way home. As we watched the flames turn the banquet to ash, it dawned on me that this was precisely the right way to assault the gates of Hell. If Jesus is truly Lord, why shouldn’t we cast out demons with whoops and hollers, instead of apprehension and dread?

Jesus is Lord, of course. He scatters the darkness, sets captives free, opens blind eyes and gives an entirely new start in life to anyone who trusts in Him. And He doesn’t stop there.

Before He left earth, he told the apostles that he was going to build a splendid home for all His friends, “a house not made by hands, eternal in the Heavens.”

To me that sounds like a Place even better than the Llajta.

Thank you for your interest in my blog. It is now a chapter in my new book Southward Bound, The adventure and wonder of road trips through Latin America, available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com.

Thank you for your interest in my blog. It is now a chapter in my new book Southward Bound, The adventure and wonder of road trips through Latin America, available in paperback and Kindle versions on Amazon.com.

BTW, you can order the paperback book at 30% off the retail price from Ingramspark. Click here to go to the purchase site.

Thank you!

Dave Miller